What is Genre?

June 21, 2022

A concept that has been popping up in recent posts is genre. It’s not surprising, as genre is central not only to film–one of my main interests–but to rhetoric and writing studies, my academic field. But what is genre?

Like most concepts that are obvious and apparent to the general public, genre has been complexified by academics in ways both productive and unproductive. Readers of other posts have likely noticed my skepticism toward academic discourse. But this skepticism has less to do with the common criticisms of overly-fancified writing and more to do with the circulation (or lack thereof) of said writing. I am, as it is sometimes pejoratively called in the academy, a “theory bro,” but only because I think theory has something to offer, not because I think it’s the way toward a rewarding academic career. To offer something, though, ideas need to circulate.

So, this post will take a “beginner’s mind” approach to the concept of genre. I’ll start with an idea that seems simple and discuss its value in understanding texts, art, and cultural production.

My overall point: Genre is a method of classification.

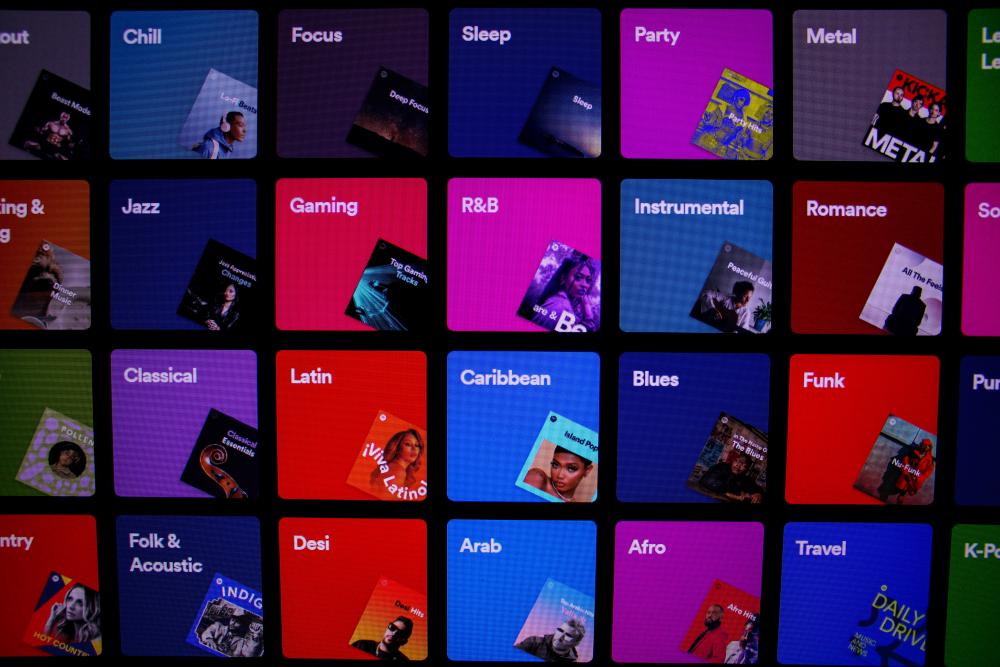

We all have a sense of what classifications are. It’s a nice word for sorting stuff. When we look at our books and weigh whether to sort them by author, by title, or by color, we’re considering classifications. When we listen to RapCaviar on Spotify, we assume that the songs all fit our classification scheme for rap. When we think about what movie we want to go see in the theaters, classifications like “horror,” “action,” and “romance” help us make decisions about which film to choose.

Often, we take classifications at face value. It would be somewhat taxing, every time we put on a movie, to first go and research all of the different decisions that went into classifying it. Yet, this work is a necessary part of classifying. As Geoffrey C. Bowker and Susan Leigh Star pointed out, classifications are invisible until people start arguing about them (Bowker and Star 2).

It’s easier to simply accept that we know what Hip-Hop is until Drake puts out Honestly, Nevermind and everyone notices that it’s a House album. But it’s on RapCaviar. And it’s a central focus of Hip-Hop media. If you look online, there are a lot of arguments not only about whether the album is good, but what it is. The classification, the genre, has become contentious.

But genres aren’t exactly the same as classifications. They’re different words, after all. Honestly, though, I find it difficult to sort out the two terms. In popular use, genres are clearly used to parse classifications of art. Musical genres, film genres, and literary genres seem like the most familiar employments of the term–maybe in that order.

But, as always, scholars have made the term more complex. And, as always, this has positives and negatives. In rhetoric and writing studies, a broad overview would reveal genres as ways to classify different types of communication–both oral and written.

Carolyn Miller, arguably the definitional figure in what’s been termed rhetorical genre studies (or, sometimes North American genre studies), claimed that genres are better understood as a way we “do things” with our communication. We rely on our knowledge of genre when we write, say, a workplace memo in order to make that memo successful. One of the examples I use for my students is asking them to consider appealing to their boss for a raise, but instead of a formal letter, writing them a poem. The content could be exactly the same, but if it were written in stanzas, it would break the boss’s genre expectations, which depend on a range of contextual factors in the workplace. The classification would become contentious.

Miller argues that genres aren’t just taxonomies but ways of analyzing communications based on audiences and contexts (49). I agree, though I sometimes feel that her perspective underemphasizes the ways that genres are used in taxonomic ways. Understanding genre relies on a sort of taxonomic fantasy: we know that every horror movie will be different, but we have an imagined sense that all horror movies share “something” that ties them all together. This something may be a set of shared features or a prototype example (Bowker and Star 62-63), but genres (and classifications generally) are like asymptotes: they can approach a coherent “grouping”–and be highly useful as they do–but never fully achieve it. Something will always “slip out” of the genre; difference will always emerge.

What is decidedly not fantastical, though, is that industry practices absolutely rely on the audience’s expectations for coherent genres. Further, those same practices also produce those expectations. Consider two ways of looking at film genres offered by Rick Altman.

-

Critics will usually begin with an awareness of an already existing genre, think about which films are already discussed as examples of this genre, and analyze their shared features. This perspective may be interesting, but it doesn’t actually explain much about where the genre comes from in the first place. It leaves out the work of how the classification came to be.

-

By contrast, producers begin with an already successful film. They say to themselves: “Hey, I would like to make more of that sweet, sweet money.” They replicate aspects of the film that were well-received in new productions, gradually building up the audience’s expectations for repeated motifs, themes, and formulas across films. Eventually, a classification emerges in the form of a genre to market these films, usually branching out from an already-existing genre (Altman 38). The genre classification, from this perspective, is a result of both the work of industrial practices and the emerging audience expectations. The fantasy of taxonomy emerges at the end of this process a market for the film industry.

Obviously, genres are useful. They help us make decisions about films to see, about books to read, about music to listen to, etc. Yet, as much scholarship has tried to point out, looking at their histories forces us to consider just how “objective” a genre classification could ever be. Beyond academic discourse, why is this useful or interesting? I’ll offer a few points in relation to film.

- Making genre classifications contentious can help us see when individual films are doing something interesting or different within their own marketed genres, as I discussed in my recent post on Men.

- We can better understand how our own perspectives on genres have been shaped by our film experiences and how we (often unconsciously) classify films based on those experiences. We can take this both in terms of how industries have shaped our ideological expectations AND as a way of pointing out just how rich and diverse the history of film truly is. We don’t have to choose.

- Finally, and this certainly deserves its own post in the future, the history of genre classifications is often, itself, the content of films, and a better understanding of genre can enrich our appreciation of those films.

Works Cited

- Altman, Rick. Film/Genre. Palgrave Macmillan, 1999.

- Bowker, Geoffrey C., and Susan Leigh Star. Sorting Things Out. MIT P, 1999.

- Miller, Carolyn R. “Genre as Social Action.” Landmark Essays on Rhetorical Genre Studies, edited by Carolyn R Miller and Amy J. Devitt, Routledge, 2019, pp. 36–54.